Main Menu

“Trust, but verify.” As scientists, this is the guiding principle that drives us to continually unpack questions to further our understandings of how things work.

For us, “trust, but verify” as a concept is critical because research evidence in its varying forms can impact practice decisions, program development, operations, and organizational policies. Indeed, “relevant, high-quality quantitative and qualitative” research evidence is a crucial ingredient to the evidence-informed decision-making process.

Experience has taught us that to incorporate the strengths of all these various evidence sources, policies and decisions regarding population health are best informed by a synthesized body of evidence rather than single studies. Knowledge synthesis is vital because single studies, even if high quality, do not necessarily take into consideration all of the factors and context necessary for decision-making at a population level. Furthermore, limited or weak evidence can lead to KT messaging that focuses too narrowly on single findings that lack nuance and provide incomplete understandings on a given topic.

In a past blog post, we initiated a discussion on the growing importance of knowledge synthesis and knowledge translation for informing the policy-making and policy implementation process. This week, to illustrate the importance of knowledge synthesis to knowledge translation and evidence-based policy-making, we are looking at highly publicized instances of evidence being put on trial in the world of nutrition policy:

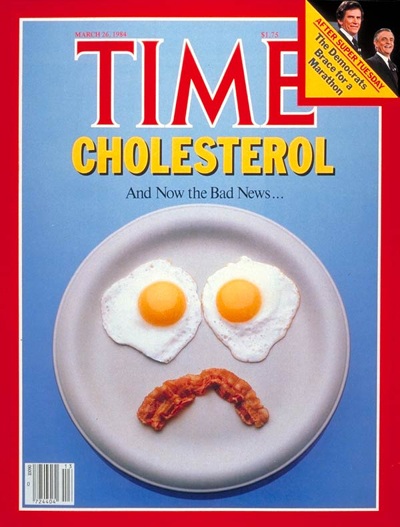

Knowledge synthesis can assess the quality of research methods and the strength of the evidence. The persecution and redemption of “the egg” is a fantastic example of this.

Dietary cholesterol is the principal steroid found in animal tissues. Our primary food sources for cholesterol include egg yolks, shrimp, beef, pork, poultry, cheese and butter.

The long believed linear or direct relationship between dietary cholesterol intake and increased risk of various forms of Cardiovascular Diseases (CVD) including but not limited to Coronary Artery Disease, Heart Failure and Stroke, was initially established through longitudinal observational cohort studies.

Important prospective observational studies, such as the Framingham Heart Studies, published results during the 1960s and 1970s that specifically associated this increased risk of Coronary Artery Disease with high cholesterol intake and identified eggs as a primary culprit due to its cholesterol content.

This study, along with the results of other observational studies led to beliefs that lasted decades and resulted in nutrition guidelines, worldwide, that cautioned against eating eggs to lower CVD in healthy and at-risk populations.

Were the initial studies flawed? Not at all. Those initial studies were pertinent for adding to that global body of knowledge and our general understanding surrounding cardiovascular disease risk and how factors like diet, exercise and smoking affect heart health; however, there was a need to understand the limitations of the studies and to conduct much more research before informing and rolling-out population-based policies and guidelines. An example of a significant limitation on these single studies included the presence of confounders.

What do I mean by confounders? The foods we consume can contain many different types of fats . A classic eggs benedict is a guilty pleasure of mine. Yes, a benny has eggs, but it can also have other ingredients that might contain saturated and trans fats (like bacon or ham).

The cooking method can also influence the types of fats found in food. In those initial observational studies, researchers were focused on one kind of fat: cholesterol, and although increase cholesterol in the blood is associated with a higher risk of CVD, there were no studies at the time to show that dietary intake actually increased the level of cholesterol in the blood. The impact of saturated or trans fats were not studied in this early research but, as we know now, these other fats also significantly increase CVD risk. These hidden culprits could mislead the interpretation of those initial study results, thereby allowing dietary cholesterol to take the fall.

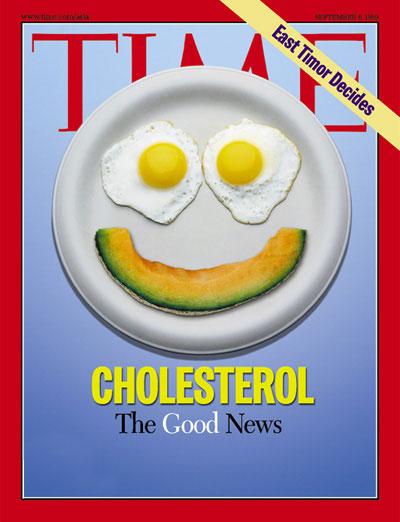

Fast-forward to today we have loads of evidence and a greater understanding of the biological mechanisms under which the body synthesizes dietary cholesterol and its implications in different populations – healthy or with co-morbid conditions. Case in point – recent knowledge synthesis studies including the latest publication from Geiker et. Al, 2018 review a variety of study designs and recommendations. This synthesis showed that eggs are a terrific source of nutrition but that there is no consensus on the cholesterol’s role in CVD risk. By looking at a variety of study designs, along with all aspects of the studies including the limitations of the study designs and the strength of the recommendations, synthesis studies offered a more nuanced understanding of cholesterol and eggs in human nutrition.

Eggs are an excellent protein source are the only dietary source of cholesterol that is low in saturated fatty acids while containing a high nutrient content and, is economically accessible. On-going research and evidence synthesis will continue to unpack its effect on serum cholesterol and its implications to the development CVD.

So our discussion about eggs made mention of a couple of “suspect fats” – namely saturated and trans fats. Much like the egg story, traditional butter made from animal fats has also undergone a similar process of “trial and prosecution” stemming from observational studies. Policies and dietary guidelines informed by observational studies led to decades of cautioning against butter consumption due to an increased risk of heart disease and stroke. Accompanying the turn away from butter was a push for the use of margarine as a healthy alternative. But is margarine better?

Studies show that butter does contain “the evil” saturated fat. However, synthesis of recent studies has shown that many kinds of margarine on the market also contain high levels of trans fats, “a greater evil” with a higher associated risk to the development of CVD. Studies also show that butter does contain many other essential nutrients that are important for maintaining health. Knowledge synthesis can be useful in conducting a multitude of comparisons to inform better decision-making in nutrition.

Similar to the egg, the story behind butter is complicated and there is no definitive answer about whether eliminating or even limiting, butter from our diet is a good idea. Butter contains unhealthy fat but may also provide other vital nutrients. Knowledge synthesis research methods have offered these nuances and will continue to unpack all of those mechanisms in which both of these products impact heart disease and health.

The examples above highlight the importance of knowledge synthesis for nutrition guideline development. However, we cannot forget the significance of translating synthesized knowledge. Early messaging around dairy in nutrition focused on fat alone. My final example shows how the single focus of fat content in milk downplayed other important nutrition considerations.

Milk, much like eggs and butter, underwent a “fat war” and faced scrutiny in the push for “low-fat” and “no-fat” which stemmed from early single studies. The main message delivered out of these early studies, to eat low/no fat diets, was based on the observed linkage between fat consumption and CVD.

Today synthesized evidence is available, unpacking the nutrient content and associated benefits of whole-fat dairy . Such benefits include richness in probiotics and essential fat-soluble vitamins A, D and K. Synthesis reviews have also shown that low-fat dairy increases circulating triglycerides (one of those suspect fats), doesn’t lower calorie intake, and can often contain added sugar (a whole other problem!).

There are no formally established associations between the consumption of whole-fat dairy, CVD, and weight gain.

These examples illustrate how evidence isolated from findings in the broader field of research, can lead to poorly informed messaging and policy. Nutrition science tends to be communicated as black and white, but it is often not as simple as that. In these cases, the focus on cholesterol and animal fat, messaged as “bad fats”, did resonate with the public and policymakers. Dietary guidelines encouraged people to limit bacon, eggs, and butter, and the public complied. However, they replaced these fats with hydrogenated (i.e. trans fat) oils and sugary “diet” versions of food. This messaging is now changing to reflect a more nuanced understanding of fats that focus on healthy amounts of different fats as opposed “good” and “bad” fats. The full spectrum of these changes is not clear as implications of policies developed on primary studies not only impact health recommendations and nutrition guidelines, but flip-flopping policies may be impacting public trust in science.

I don’t believe that the problem lies in the research process alone. Nutrition, science and policy alike require collective thinking about the human experience and local context to effectively inform health recommendations. Knowledge synthesis, and by extension knowledge translation, has a place in that collective approach: to provide the capacity to unpack what we know, need to know and how to translate and utilize that information in a way that is most accurate and meaningful.

Disclaimer: This article is NOT a nutrition advice piece. Please ensure you solicit nutrition advice from professional and licensed personnel that considers your individual and contextual predispositions.

Until next time!

Let us know how you want to stay connected

News + Events

News + Events

Patient Partner Research Opportunities

Patient Partner Research Opportunities

I agree to receive occasional emails from AbSPORU.

I agree to receive occasional emails from AbSPORU.University of Calgary Foothills Campus

3330 Hospital Dr NW

Calgary, AB T2N 4N1

College Plaza

1702, 8215 112 St NW

Edmonton, AB T6G 2C8

The Alberta SPOR SUPPORT Unit operates on and acknowledges the lands that are the traditional and ancestral territory of many peoples, presently subject to Treaties 6, 7, and 8. Namely: the Blackfoot Confederacy – Kainai, Piikani, and Siksika – the Cree, Dene, Saulteaux, Nakota Sioux, Stoney Nakoda, and the Tsuu T’ina Nation and the Métis People of Alberta. This includes the Métis Settlements and the Métis Nation of Alberta. We acknowledge the many First Nations, Métis and Inuit who have lived in and cared for these lands for generations. We make this acknowledgment as a reaffirmation of our shared commitment towards reconciliation, and as part of AbSPORU’s mandate towards fostering health system transformation.

© 2024 AbSPORU