Main Menu

Using different communication methods, beyond the journal publication and conference circuit, can be an effective way to increase the impact and reach of research evidence. Not only is this true when trying to communicate with the public, but also when engaging with colleagues and other stakeholders. As such, researchers are being increasingly encouraged to use methods such as social media, stories, podcasts, and YouTube videos in their knowledge dissemination efforts. However, with many other pressing obligations, time is at a premium for most investigators. Venturing outside of their communication comfort zone is often seen as an intimidating endeavor that will take away too much time and/or resources.

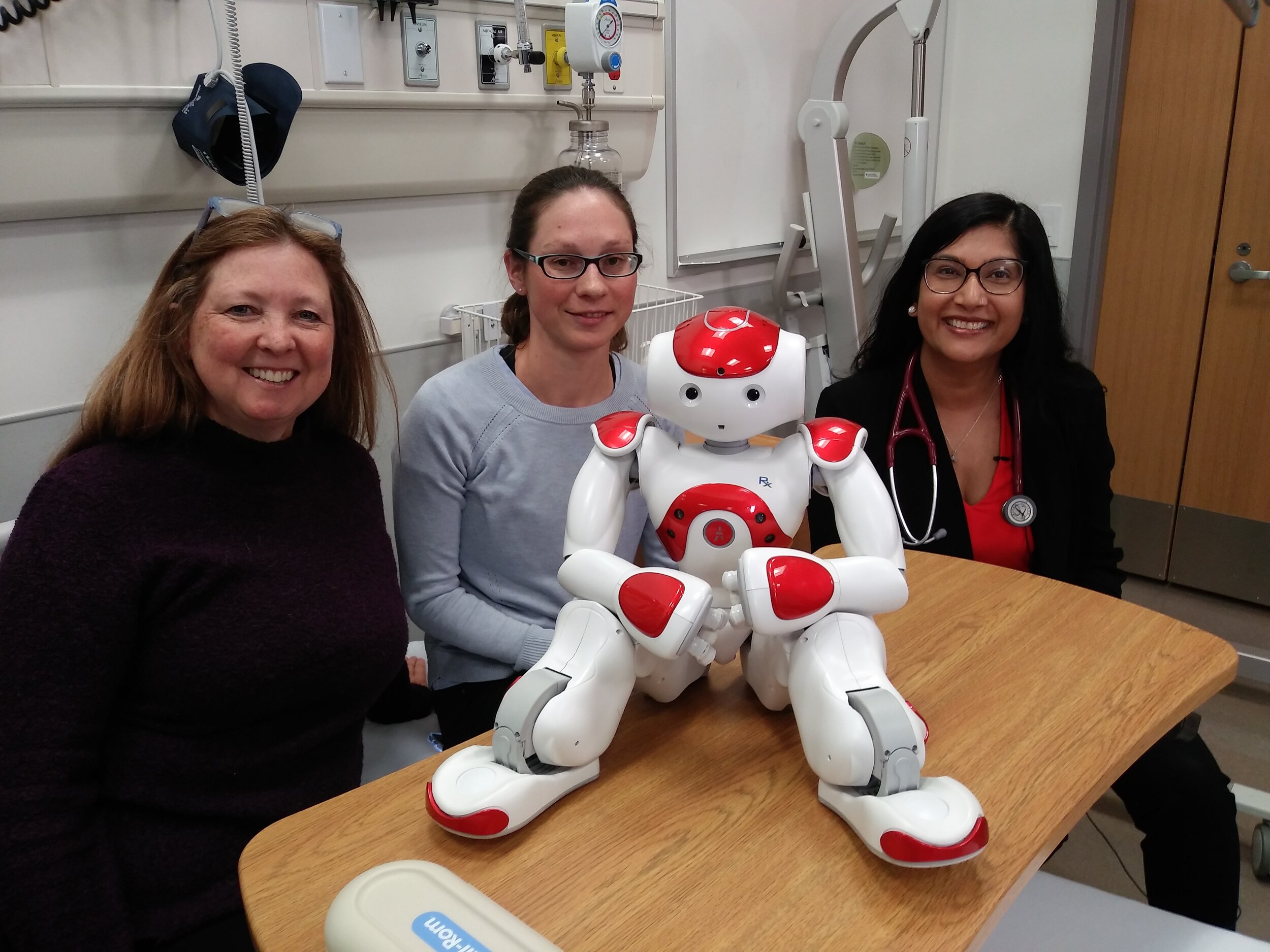

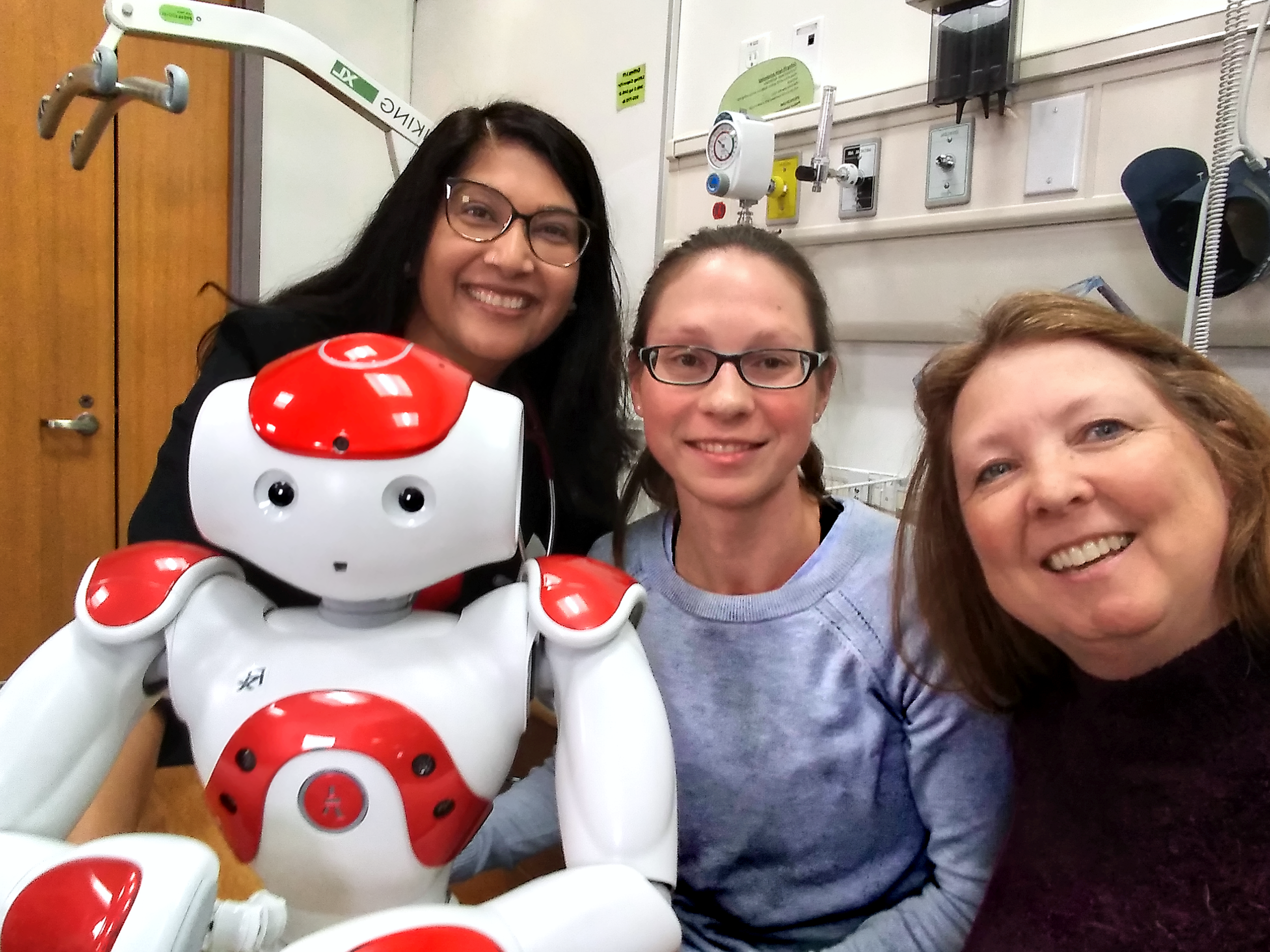

Recently, a group from the U of A’s Department of Pediatrics took the plunge and decided to make a video abstract for their publication “Digital Technology Distraction for Acute Pain in Children: A Meta-analysis” which was recently published in Pediatrics. The result was an engaging four-minute video where Medi the robot interviewed the senior author, Dr. Samina Ali. KT Alberta sat down with two of the authors, Dr. Michelle Gates and Dr. Samina Ali, to discuss the process of making this video abstract, and to ask if they had any advice for other researchers who are thinking about making one themselves.

Like many other journals (e.g. BMJ Journals, Sage Publications, JCI, etc.) Pediatrics provides guidelines and options on how to make a video abstract. The simplest option is for the investigator to record themselves outlining their research verbally, using a cell phone. The simplicity of this option makes the video abstract possible for any researcher, and therefore it is a commonly chosen format. When the U of A team was asked to make the video abstract though, they decided to try something more elaborate even though they knew it would take more time and effort.

The team was given a deadline of three months to make the video abstract, and both agree that time span was needed to make all of the necessary arrangements. Spread over those three months, however, they estimate they committed a total of 24 hours of their time to make the video abstract.

Filming of the abstract itself took around 1.5 hours, and the result was a professional looking and sounding video. The team credits this to the audiovisual expertise they found at the U of A’s Centre of Teaching and Learning (CTL).

Both agreed that without the services of the CTL, they would have had to choose a much simpler format for their video abstract. As well, either more time would have been spent finding expertise at a cost that fit their budget, or the quality would have decreased as they would not have had access to sophisticated recording equipment or professional film editing.

The Wiley Network states that articles with video abstracts have 82% more full-text downloads. Although they don’t know the impact of the video on their publication’s readership numbers, This team knows that the reach of their message is expanding through social media. Since the video was posted on Twitter and Facebook in mid-January 2020, it has been shared internationally and it is still being retweeted one month after. All of the feedback has been very positive so far, and colleagues and friends have been eager to share it on their own social media channels. The team sees the video abstract as a versatile tool that could be used in many different ways for the long term.

The team is satisfied with the final product and the excitement it has generated, but they admit they already know what they would do differently next time. While making the video, they found it challenging to fit all of the information they wanted to include within the 4-minute limit. However,

Both agree in the future, they would limit any video abstract to 2 minutes, or shorter, with the take-home message stated within the first 30 seconds. To do this they would focus less time on outlining the rigor of their methods and just focus on the main results that they really want those watching the video to remember.

Both agree that the time and effort they committed to the video abstract was worth it, and they encourage other researchers to try to “engage their inner Hollywood.” For researchers thinking about making a video abstract, Michelle and Samina offer the following advice:

For health researchers in Edmonton, the focus of the CTL is to provide resources for teachers at the U of A, including audiovisual expertise for online courses. However, they are able to assist with video abstracts on a cost-recovery basis, depending on their capacity at the time of the request. For more information contact ctl@ualberta.ca.

For health researchers in Calgary, audiovisual support for making video abstracts are at AV Services at the Foothills Hospital Campus. For more information, you can contact their videographer, Scott Giffin.

Let us know how you want to stay connected

News + Events

News + Events

Patient Partner Research Opportunities

Patient Partner Research Opportunities

I agree to receive occasional emails from AbSPORU.

I agree to receive occasional emails from AbSPORU.University of Calgary Foothills Campus

3330 Hospital Dr NW

Calgary, AB T2N 4N1

University of Alberta North Campus

Edmonton Clinic Health Academy (ECHA)

11405 87 Ave NW

Edmonton, AB T6G 1C9

The Alberta SPOR SUPPORT Unit operates on and acknowledges the lands that are the traditional and ancestral territory of many peoples, presently subject to Treaties 6, 7, and 8. Namely: the Blackfoot Confederacy – Kainai, Piikani, and Siksika – the Cree, Dene, Saulteaux, Nakota Sioux, Stoney Nakoda, and the Tsuu T’ina Nation and the Métis People of Alberta. This includes the Métis Settlements and the Métis Nation of Alberta. We acknowledge the many First Nations, Métis and Inuit who have lived in and cared for these lands for generations. We make this acknowledgment as a reaffirmation of our shared commitment towards reconciliation, and as part of AbSPORU’s mandate towards fostering health system transformation.

© 2025 AbSPORU